September 11, 2025

Frances Glessner Lee: The Mother of Modern Forensic Science

September 11, 2025

Frances Glessner Lee: The Mother of Modern Forensic Science

How a determined socialite, inspired by true crime, helped professionalize the field of murder investigations.

Episode Description

Frances Glessner Lee discovered her true calling later in life. An heiress without formal schooling, she was in her fifties when she transformed her fascination with true crime and medicine into the foundation of a new field: forensic science. In the late 1920s, she drew inspiration from a family friend, a medical examiner involved in notorious cases—including the infamous Sacco and Vanzetti trial.

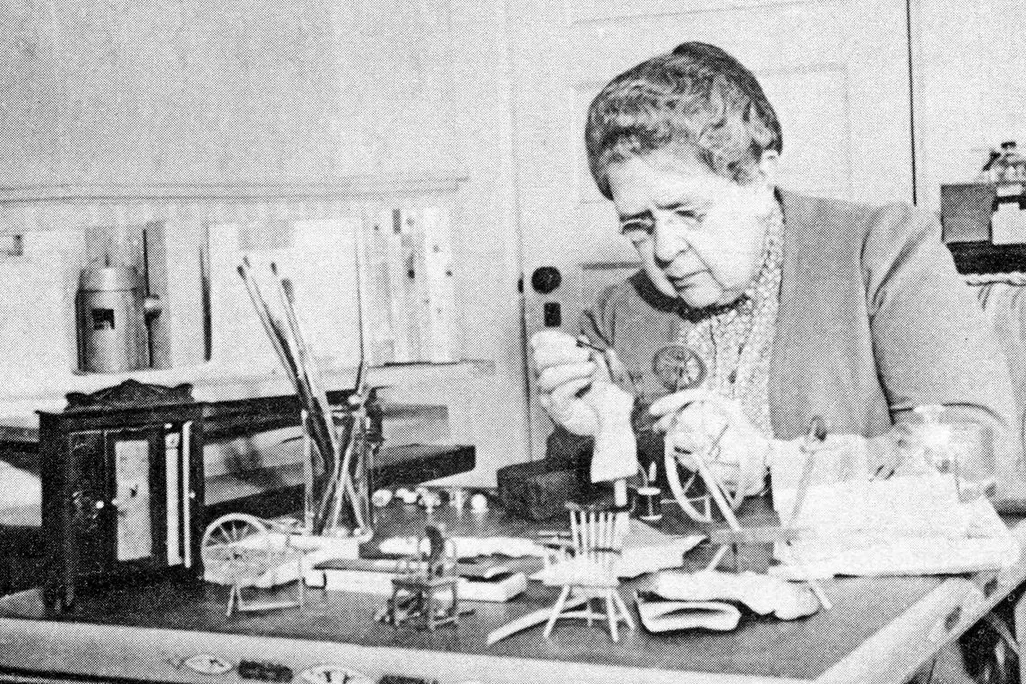

For Glessner Lee, the puzzle of untangling the truth about violent deaths proved irresistible. She recognized that solving crimes demanded both rigorous methods and professional training. She funded and helped found the Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard University. Her most unusual teaching tool: intricately crafted dollhouse dioramas depicting grisly crime scenes.

Katie is co-founder and co-executive producer of The Lost Women of Science Initiative. She is the author of six nonfiction books and one novel, and was a longtime reporter for The New York Times. She is at work on her second novel.

Marcy is an award-winning audio producer who has covered science, technology, history, culture, sports, business, and celebrity chat. Her work can be heard on Next Question with Katie Couric, Overheard at National Geographic, and Note to Self (WNYC), among many others.

Katie is co-founder and co-executive producer of The Lost Women of Science Initiative. She is the author of six nonfiction books and one novel, and was a longtime reporter for The New York Times. She is at work on her second novel.

Marcy is an award-winning audio producer who has covered science, technology, history, culture, sports, business, and celebrity chat. Her work can be heard on Next Question with Katie Couric, Overheard at National Geographic, and Note to Self (WNYC), among many others.

Kristen Frederick-Frost is a curator in the Division of Medicine and Science at the Smithsonian Institution.

Former executive assistant to the Chief Medical Examiner for the State of Maryland, is the author of 18 Tiny Deaths: The Untold Story of Frances Glessner Lee and the Invention of Modern Forensics.

Jeffrey Jentzen is professor emeritus at the University of Michigan, departments of Pathology.

Further Reading:

18 Tiny Deaths: The Untold Story of Frances Glessner Lee and the Invention of Modern Forensics, by Bruce Goldfarb, Sourcebooks, 2020.

OCME: Life in America’s Top Forensic Medical Center, by Bruce Goldfarb, Steerforth Press, 2023.

The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, by Corinne May Botz, The Monacelli Press, 2004.

Episode Transcript

Frances Glessner Lee: The Mother of Modern Forensic Science

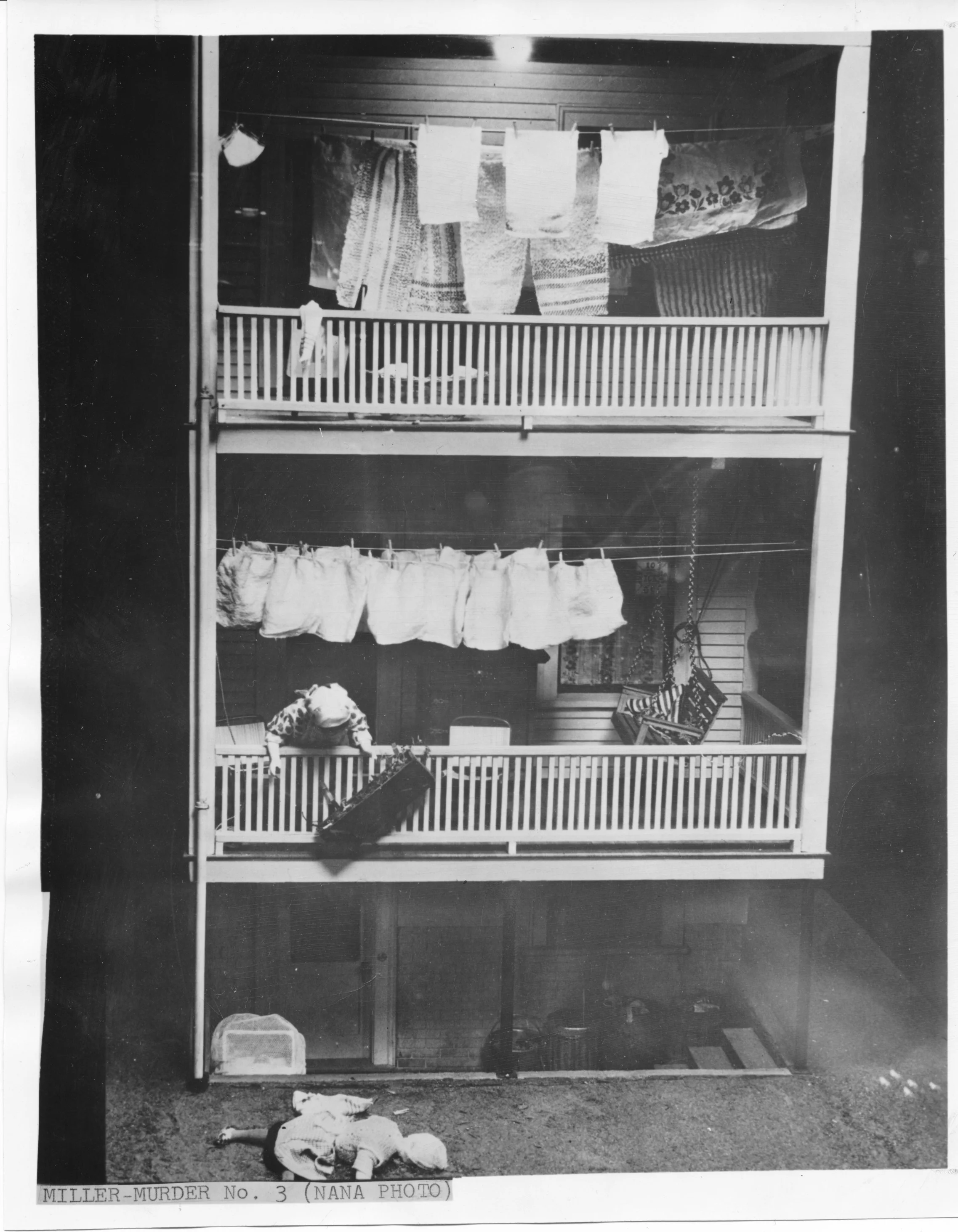

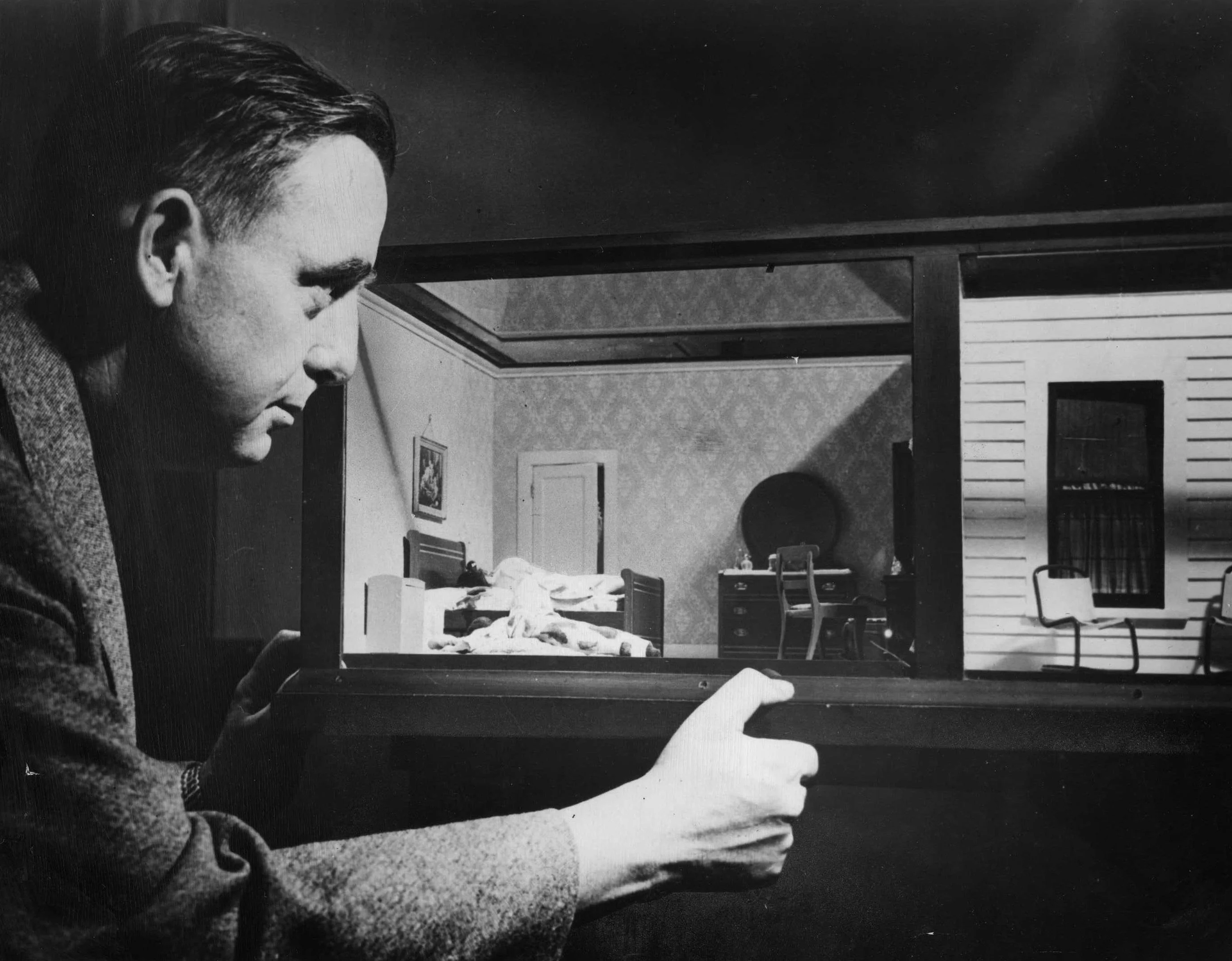

Katie Hafer: The murder took place in the room of a cabin. It's an unremarkable room. A few pieces of furniture, a blue and white linoleum floor, all typical of the early nineteen hundreds. It is unmistakably rustic with unadorned timber walls. There are no signs of domesticity except a calendar. Its pages are curled up at the bottom. It shows the month is August. A single wooden chair is tipped over and across from a cast Iron stove is a scene of abject horror. The charred remains of a body lie on top of a badly burned bed. Only a few blackened timbers are left to hold up the roof, and at the foot of the bed is an alarm clock, sitting on a singed dresser.

This isn't an ordinary murder scene. It's actually a diorama. It has every characteristic of a dollhouse, but it's more than that. It's a dollhouse sized, three-dimensional reconstruction based on the 1916 murder of Florence Small, the woman in the bed who was murdered by her abusive husband. Frederick Small killed his wife. Then using a chemical accelerant and an alarm clock rigged to create a spark, he set a fire to destroy the evidence all while he was miles away. What Frederick Small didn't count on was that an entirely new discipline was being developed called forensic science, one that could prove that Florence Small wasn't the victim of a random accident as many might have thought. From then on Frederick Small and many monsters like him would no longer be able to get away

Today on Lost Women of Science, senior Producer Marcy Thompson and I are going to piece together the story of the woman who created this perfectly rendered murder scene and the many other Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death as they were called. Her name is Frances Glessner Lee. She was born into incredible wealth in the late 19th century. She had no formal education and very little was expected of her. And yet she championed a brand new field, forensic science where scientific knowledge is employed in service of criminal and legal investigations. Along the way, she pioneered new death investigation techniques, forged unlikely alliances, faced social and cultural obstacles, and helped foster what would become our lasting obsession with true crime.

Although there might be a few of you out there who are familiar with Frances Glessner Lee's gory dollhouses, there's very little understanding of who Frances was and more importantly, why she did what she did. Today we investigate why a woman of such social distinction and refinement became absolutely obsessed with

Hey, Marcy Thompson.

Marcy Thompson: Hey, Katie.

Katie Hafer: Is it fair to say you take a certain amount of joy in finding subjects who are especially lost?

Marcy Thompson: Absolutely. If I hadn't become a reporter, I probably would've been a detective. I love following clues, turning up evidence. It's incredibly rewarding, and it was especially true in putting this episode together.

Katie Hafer: And why is that?

Marcy Thompson: Well, the story of Frances Glessner Lee is kind of like a whodunnit inside of a whodunnit. She was totally instrumental in starting the field of forensic science, but she herself remains kind of a missing person. She was a mysterious figure who deliberately, and not so deliberately, stayed behind the scenes.

Katie Hafer: So what, what do you mean by mysterious?

Marcy Thompson: Well, she was an unlikely suspect to be drawn into this field in the first place, which we'll talk about more for sure. But unlike other stories I've worked on for this podcast, what isn't totally apparent was her motivation

Katie Hafer: Ah, motive. That's a key part of any whodunnit. We need to understand why she did what she did.

Marcy Thompson: Right. So following a person's motivation is usually what helps us, um, reveal the outlines of a lost woman scientist's work. There's usually something that sparks them, but the thing driving my curiosity with this story is different.

Katie Hafer: It seems. Correct me if I'm wrong, but it seems that Frances Glessner Lee is best remembered for her nutshell studies of unexplained death. That's what they were called formally, right?

Marcy Thompson: That's right.

Katie Hafer: And these sort of dioramas of doom that she created with little bodies and tantalizing clues.

Marcy Thompson: I mean, those were developed as teaching aids. They were used to train death investigators and that's, they were developed to teach people to look very methodically at every detail of a crime scene. Those dioramas give some people the impression that Frances was an odd woman, obsessed with like a kind of …

Katie Hafer: okay, yeah, I get that.

Marcy Thompson: Yeah. Like a macabre arts and crafts, but the nutshells tell only a small part of her stor. To understand what drove her to make them. I had to figure out what made her obsessed with crime in the first place.

So in search of clues, I made a trip to Washington DC.

I'm heading inside the Smithsonian Museum of American History. It is a miserably rainy day, and it seems that every tourist visiting Washington DC today is inside this building, including busloads of very hyped up school children.

They're here to see the Ruby slippers worn by Judy Garland in the Wizard of Oz, or the droids from Star Wars, but I'm here to find a clue.

I take the escalator up one flight and find my way to a small exhibit on the second floor. Suddenly the mood has shifted.

Kristen Frederick-Frost: It's a very quiet space. People are kind of contemplative, that really speaks to the power of these objects to draw people in.

Marcy Thompson: I can already tell that this is no ordinary collection of historical artifacts.

Kristen Frederick-Frost: Right now we're in the Albert Small Documents Gallery, and it's an exhibit, called Forensic Science on Trial.

Marcy Thompson: The display cases are filled with objects from some of the most notorious crimes in US history, but they're complicated objects, objects that don't always tell the whole story.

Lucky for me, the person I came here to meet isn't any ordinary guide.

Kristen Frederick-Frost: My name is Kristen Frederick-Frost. I'm Curator of Science here at the National Museum of American History.

Marcy Thompson: True crime stories are everywhere and in our cultural fascination with crime solving, we tend to place a lot of faith in the irrefutability of evidence, but we sometimes forget how circumstances both personal and historical might influence an outcome.

Kristen Frederick-Frost: Science is a people product, and nowhere does that come out more than in forensic science because you have to argue whether or not the data and its interpretation, analysis is something that is convincing.

Marcy Thompson: Kristin Frederick-Frost might not realize it, but she just revealed trace evidence of Frances Glessner Lee, sometimes called the mother of forensic science.

Frances Glessner Lee dedicated her life to standardizing an approach to death investigation. And it wasn't easy for Frances or for Kristin Frederick Frost, who had the job of assembling this exhibition.

Kristen Frederick-Frost: I really wanted to pack a lot into this a thousand square foot room.

Marcy Thompson: Strangely enough, Frances Glesner Lee was also preoccupied with packing a lot into small spaces, and her approach was formidable and exacting. Even the smallest details didn't escape her attention.

Tell me, um, a story if you have one, or what was the weirdest, hardest object in here to find? What kept you up at night the most when you were searching high and low for, for stuff?

Kristen Frederick-Frost: The hardest one to find, uh, is we're actually sitting in front of it. I really wanted to find the firearms evidence from the Sacco and Vanzetti case.

Marcy Thompson: And there's the clue I'm looking for right in front of me.

Kristen Frederick-Frost: So you have, uh, the pistol up here and these are the grips likely made of Bakelite, it was an early plastic.

Marcy Thompson: Two Italian immigrants, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were convicted of robbery and murder in 1921. Their case became a cause celebre and a polarizing one. At that it raised issues of social justice, political radicalism, and highly questionable legal tactics. It all boiled down to who actually fired that pistol …. And describe the, the little bullet there.

Kristen Frederick-Frost: It's pretty little. I was surprised when I first held it in my hand

Marcy Thompson: This tiny bullet proved deadly and it would change the way we look at death investigation forever. …. And this is bullet number three?

Kristen Frederick-Frost This is bullet number three.

Marcy Thompson: It was removed from the body of Alessandro Berardelli, a security guard murdered during the robbery of a shoe factory in Braintree, Massachusetts. By the time the trial was over, the entire world would weigh in on this evidence.

Kristen Frederick-Frost: The question of whether or not that bullet was fired from that gun becomes central to the case.

Marcy Thompson: The man who removed this bullet was George Magrath, the medical examiner for Suffolk County, Massachusetts. Magrath testified that this very bullet severed the great artery leading from Berardelli’s heart – testimony that would help seal Sacco’s fate, eventually sending both defendants to the electric chair. The presence of bullet number three would seem like a closed case, but even more than 100 years later, there still isn't closure.

Leaving the exhibit and heading back out into the rain. I remember that George Magrath was a longtime friend of the Glesner family. So I had to ask myself, how did a controversial robbery verdict in Boston change the life of a wealthy socialite from Chicago? And, the way we now understand homicide investigations?

Even though Frances Glessner Lee was nowhere to be found in the Smithsonian Gallery, I just visited, her fingerprints were everywhere. Maybe just, maybe it was bullet number three that sparked the motivation of Frances herself.

Katie Hafer: Okay, you have hooked me. It looks like Frances' motivation was bound up in figuring out how the objects at a crime scene can lead to solving a mystery. But before we go on, let's try to get a better handle on Frances, like she was born when and where? She was born in 1878 in Chicago. It was a city that was growing rapidly.

And what kind of kid was she? I mean, where, where are the clues there?

Marcy Thompson: She was quirky after having her tonsils out when she was nine years old. She decided to follow local doctors around on rounds and in her little playhouse, she would make concoctions for the doctors, little remedies for various ailments.

And this led, uh, to a lifelong fascination with medicine.

Katie Hafer: Oh, I love this so much. So did Frances, did she wanna become a doctor herself?

Marcy Thompson: Yeah. I mean, that seems to be the case.

She wrote later in life that she was deeply interested in medicine and nursing, and she would've enjoyed training in either one.

Katie Hafer: But she didn't because,

Marcy Thompson: Because that isn't by and large what girls set out to do at the turn of the 20th century. I mean, she loved music. She loved to make things with her hands, which is something girls at the time were encouraged to do.

Later on, she actually created a miniature of the entire Chicago Symphony Orchestra to scale, and she gave that to her mother on her birthday.

Katie Hafer: Oh my gosh. So itty bitty violins and oboes and Oh my

Marcy Thompson: God. Yeah. In little outfits.

Katie Hafer: Little outfits. So it sounds like the family was very well off.

Marcy Thompson: Yeah. Frances' father was a partner in what would become one of the largest manufacturing companies in the world at that time, International Harvester.

And that made the Lee family one of the wealthiest in Chicago. They had a mansion on Chicago’s South Side, which still exists, and a massive estate in the White Mountains of New Hampshire.

Katie Hafer: And I'm assuming that education was important to these people.

Marcy Thompson: Yeah, very important. Frances and her brother George were both taught by amazing tutors. They learned math and natural sciences. They learned multiple languages, music and art. But as I mentioned, Frances wasn't able to pursue a career in medicine. Uh, she once wrote simply, “This was not possible.”

Katie Hafer: Oh, geez. I mean, this unfortunate refrain is one that we hear over and over again at Lost Women of Science.

Marcy Thompson: Yeah, it is. And even though there were some women at the time who did go to college, that wasn't to be the case with Frances. But her brother George, on the other hand, did go to college, to Harvard, in fact, the gold standard in the Glessner family. He thrived there and would bring his college friend George Magrath home over breaks.

Katie Hafer: Ooh. So the same George Magrath, the Medical Examiner from the Sacco and Vanzetti case.

Marcy Thompson: That's right. That's right.

Katie Hafer: Huh…

Marcy Thompson: So the two, Georges brother, George, and friend George would be at the Glessners during those long breaks. And you kind of have to wonder what it was like for Frances to sit there and hear about their college exploits.

Katie Hafer: So what did she do? What did she do instead of college? Wait, I think I can guess.

Marcy Thompson: I'm sure you can. When she was 19, she was married off to a 30-year-old attorney from Mississippi named Blewett Lee. They had three children, but it was not a good marriage. They divorced in 1914 and she was by all accounts pretty depressed for the 17 years they were together and she continued to be depressed well after their divorce.

Katie Hafer: Oh, geez. So, okay. Right. Take a smart, young woman, encourage her to learn about the world and then prevent her from having a career of her own that is just so not okay.

Marcy Thompson: But the crazy thing is I think that her love of medicine and her frustration with this double standard actually contributed to her motivation. It's kind of part of what drew her later in life to legal medicine, which was her passion, and she forged that on her own terms.

Katie Hafer: Ah, yes. Okay. How do we go from sad, rich, divorced woman to driven yet formally uneducated proponent of forensic science? This is a story I've gotta hear.

Marcy Thompson: And interestingly enough, that will lead us directly back to George Magrath.

Katie Hafer: Uh, George Magrath, the best friend slash Sacco and Vanzetti Medical Examiner.

Marcy Thompson: Yes … when we come back, I’d like to share some of my conversation with an expert on forensic medicine and Frances Glessner Lee. In fact, he wrote the book on her.

BREAK

Bruce Goldfarb: My name is Bruce Goldfarb, but I am an author in Baltimore, Maryland.

Marcy Thompson: In addition to writing about Frances Glessner Lee, Bruce Goldfarb worked for the Chief Medical Examiner for the state of Maryland, which is where the nutshell studies of unexplained death are currently housed.

Bruce Goldfarb: As a, a fan of Frances Glessner Lee, when I was going through her papers and everything, it was like I was reading the story for the first time and learning these things, and it was really extraordinary experience.

Marcy Thompson: To understand what drove her and what would connect her to George Magrath. You have to go back and understand who was responsible for determining the cause of unexplained death. At the turn of the 20th century, the United States was not a great place to die unexpectedly … in the US at that time. Death investigation was problematic.

A suspicious fall down a set of stairs might be investigated by a coroner if it was investigated at all. The coroner was a holdover from the British crowner, who collected money for the king – including debts, in the case of death – and a version of that system was put into place in the United States where coroners had no required medical training and most had no education at all. They were elected officials whose findings could be easily influenced.

Bruce Goldfarb: It wasn't that the best person for the job necessarily got it, it, it says that they got more votes than somebody else.

Marcy Thompson: So suddenly that push down the stairs could be declared a trip if the coroner saw it that way. When it came to solving crimes, there was no science involved because there was no science period.

Bruce Goldfarb: You don't have these tools to apply until you develop forensic toxicology and, and these other technologies that don't even exist at the time period.

Marcy Thompson: Even medical doctors at the time weren't trained to deal with cause of death. But in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, that began to change when a medical examiner's office was established and they hired none other than George Magrath, the old college friend of George Glessner, Frances' brother

Bruce Goldfarb: Magrath was a medical doctor, trained as a pathologist, a graduate of Harvard Medical School, appointed in 1907, and he was literally America's first forensic pathologist. And when he got the job, he realized that he didn't have the background or experience or education to investigate deaths. So Magrath basically took his own fellowship and he went to Europe and he spent some time in these capitals of medical training where they had developed what they called legal medicine. And then he came back to the United States and he incorporated these techniques, the scientific medical model of death investigation.

Marcy Thompson: This was cutting edge science at the time. George Magrath would preside over thousands of death investigations in the rapidly growing city of Boston and appeared on the witness stand in almost every courtroom in the northeast, including as a medical examiner who cracked the case of Frederick Small, who murdered his wife and burned down their cabin in Osippee, New Hampshire.

Small didn't count on the bed, falling through the floor, along with Florence's torso preserved in the water of Lake Ossipee that had seeped into their basement. Small thought he'd collect his wife's $20,000 insurance policy and call it a day. Instead,

While working to investigate murders and deliver testimony in court, Magrath taught some of the techniques he learned along the way to students at Harvard Medical School. But Magrath's health wasn't good.

Bruce Goldfarb: Magrath had very bad cellulitis of both hands, and that's probably from working with these caustic materials and stuff that he is working with.

Marcy Thompson: And in the summer of 1929, he checked himself into Phillip's House, a luxury wing of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston to recuperate. And who else happened to be there recovering from an unknown illness, but Frances Glessner Lee now a 51-year-old divorcee with grown children,

Bruce Goldfarb: And by 1929 she was really adrift and she was in in a doldrums, and she's recuperating at Phillip's House in Boston

Marcy Thompson: and the two longtime friends got to talking.

Bruce Goldfarb: He enjoyed telling stories and about closed cases. He would never talk about anything that he was actually working on, but these historical ones, absolutely.

Marcy Thompson: Including, it would seem, the case against Nicola Sacco and Bartolemeo Vanzetti.

It was the trial of the century after all. The defendants had been executed. Just two years before. George Magrath had witnessed their electrocution; he signed their death certificates, and in that summer of 1929, a full eight years after the verdict, newspapers in Boston were still publishing stories about whether or not Sacco and Vanzetti were guilty.

It was still very much on the city's mind and likely on George Magrath's and now Frances's.

Bruce Goldfarb: They would sit on the balcony and just talk about all kinds of stuff, and Magrath explained about his work and he explained the whole business between coroners and medical examiners. Although in popular culture, they're, the terms are used interchangeably. They're really very different positions,

Marcy Thompson: And the main reason for that difference is education. Magrath's work as with the Florence small case and many others involved a high level of training. He was practicing on a whole different level.

Bruce Goldfarb: There wasn't just a coroner problem in the Northeast. It was throughout the entire United States. The entire country, if there is any death investigation done at all, would be done by a coroner.

Marcy Thompson: The problem was reaching a tipping point and the Sacco and Vanzetti case whipped up a national conversation about necessary reforms, both legal and medical. Magrath's own role in the case was fraught. His damning testimony proved controversial, but the system was hobbled by problematic legal tactics and a lack of scientific knowledge.

Change was in order. In fact, in 1928, the summer before Frances and George convalesced at Phillip's House, a scathing report was issued by the National Research Council called the Coroner and the Medical Examiner. It recommended the abolishment of the coroner system and the development of properly equipped medical legal institutes affiliated with universities where a high level of training could take place.

Frances and George took that recommendation and ran with it, and what she did next was nothing short of groundbreaking. Inspired by her Phillips house conversations with George Magrath, which tapped into her deep admiration for the medical sciences, she set out on the long journey to build an entire department of legal medicine at Harvard from the ground up.

There students could receive a top-notch education in forensic science. They would learn the latest techniques from around the world. Frances was no longer a woman adrift. She had a purpose to use science in pursuit of justice.

Bruce Goldfarb: She started a practice of medicine.

Marcy Thompson: She poured every ounce of herself into it, and more than $250,000 of her own money equal to about $5.8 million today. The only way to fix the system was to provide education and not just any education, a medical legal education at Harvard.

Bruce Goldfarb: I mean, this is a clinical field of, you know, medical specialty just like any other specialty. And, and it did not exist before her, and she established it.

Marcy Thompson: The new field of forensic science gave Frances Glessner Lee a way to get to college and Harvard at that. But as we will find out, it was like her marriage, a union that wouldn't last.

Katie Hafer: You know, Marcy, it seems to me that like a lot of our lost scientists, Frances was making the most out of her circumstances. But in her case, her contribution to this field wasn't so much science itself, it was making a field of science possible. Is that right?

Marcy Thompson: Yeah. I mean, as Bruce Goldfarb said, she identified the need and finally she saw a place to invest her intelligence and her talent.

And it was more than just her money that made all of that possible. It was also her focus, her determination, and her drive, which was considerable.

Katie Hafer: Right, right. And I also, I also see what you mean when you said that she was, quote, behind the scenes.

Marcy Thompson: Yes, she was not out in front and she worked very hard to start the Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard, and even though she read everything and was as much of an expert in this field as anyone, she purposely stayed in the background. But the only way that she showed her true sort of talent was through those nutshell studies of unexplained death,

Katie Hafer: the dollhouse and gee, didn't it come in handy that she learned to work with her hands? Right.

Marcy Thompson: Right. Totally.

Katie Hafer: So how many of these did she make?

Marcy Thompson: She made 19 altogether.

Katie Hafer: Wow.

Marcy: And they were all. Very highly detailed recreations. Their purpose was to teach death investigators to closely observe a murder setting.

So they were meant to look at these things, spend a lot of time pouring over the details, paying attention to everything from the placement of bodies, to blood spatter, to skin discoloration. All of those kinds of gory details were there for a reason. And the purpose, this is the interesting thing, their purpose was and still is. And this is, these are Frances' words.

“Convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell.” And these nutshells that are now all restored have been used for that purpose for more than eight decades. They're still being used.

Katie Hafer: Her nutshell dollhouses are still being used.

Marcy Thompson:Yeah.

Katie Hafer: Amazing. And are they available to the public?

Marcy Thompson: No, they're not, unfortunately.

Oh. But they were, um, featured in an exhibit at the Renwick Gallery, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2018. And when they were there, the public got to see them for the first time. And what's really cool is that I spoke to the conservator who worked to restore Frances's Nutshells, and the process gave her a firsthand look at what was going on inside the mind of Frances Glessner Lee.

Ariel O'Connor: My name is Ariel O'Connor and I am an Objects Conservator and. Some people describe us as being art doctors so we can repair artwork if it's broken. Sometimes we can be forensic scientists for art, and so we can investigate how something is made and what that tells us about how it's deteriorating or the past.

Marcy Thompson: And when the nutshell studies came before you, had you ever seen anything like that before

Ariel O'Connor: I had seen dollhouses, I had seen craft, and I had never seen art material used in a way like this before. It was completely unbelievable to me that you could take something that was, uh, maybe considered a traditional feminine craft like knitting or painting, and use it to completely change the world of science, and in this case, the world of forensic science.

Marcy Thompson: And your early impressions of the project were were what? Did you look at them and say, these are so gruesome?

Ariel O'Connor: Instantly, I noticed incredible craftsmanship. Tiny pieces of clothing that I could tell were hand knit. I learned later they were hand knit with straight pins. It took Frances Glessner Lee so long to make these, she would have to rest her eyes every 20 minutes as she was working. I saw beautifully hand painted paintings, tiny cigarettes that were hand rolled, and I had never seen a dollhouse and I learned later, these are not dollhouses. These are, these are true crime scenes that you have to solve.

There's a lot of crossover between conservation and forensics, I had to take a step back and realize. Oh wait, like don't look at them as a conservator. Right. Look at them as if I were a detective approaching them and I try to approach my conservation treatment like Frances Glessner Lee would approach the forensic investigation and use material evidence as a clue to tell me whether something should be returned or changed or left alone.

Marcy Thompson: I love the fact that you're learning from her sort of from her, from the beyond about doing your own job.

Ariel O’Connor: And I felt this level of obligation to bring it back in a sense to the way that she had made them. And I absolutely feel that and feel her influence in my work to this day.

Katie Hafer: So Marcy, as you search for Frances' fingerprints, as it were, uh, on forensic science. What else did you find?

Marcy Thompson: Well, the path from those conversations with Magrath back at the Phillips House to our modern system of forensic medicine is not a straight one. So Harvard University treated Frances with a lot of disrespect. And in 1951, she actually wrote. And this is kind of great. “Harvard has a reputation of being old fogeyish and ungrateful and stupid, and I have indeed found this reputation to be deserved.”

Katie Hafer: Oh my gosh. Old fogey-ish, ungrateful and stupid. I mean, that's quite the indictment.

Marcy Thompson: I mean, she was angry.

Katie Hafer: She was angry

Marcy Thompson: And she ultimately cut them out of her will when she died in 1962 and the Department of Legal Medicine she had started there and poured her whole life's work into was actually disbanded in 1967.

Katie Hafer: Oh, it sounds like another kind of painful divorce, right?

Marcy Thompson: I mean, you could say that, but it didn't end there. So, which is a good news. I had a really interesting conversation about Frances' legacy with Jeffrey Jentzen. Jeffrey is a forensic pathologist. He's a professor emeritus at the University of Michigan in the departments of pathology and history.

He's written about Frances and her legacy. Interestingly, he was also the medical examiner in Milwaukee for over 20 years where he presided over the investigation of serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer. So he's seen more than his share of difficult crime scenes. So Jentzen started out by referencing that 1928 National Research Council report.

That was the one that Frances and George talked about back at the Phillips House. And that was the report that recommended the abolishment of the coroner system.

Jeffrey Jentzen: That 1928 report is a early milestone in the attempt to improve death investigation nationwide.

Marcy Thompson: I'm curious because I'm a little hung up on this, the Sacco and Vanzetti case, and the obvious questions that weren't ever answered. Do you think that had any part to play in this 1928 National Research Council finding?

Jeffrey Jentzen: Oh yeah. I think it did.

Marcy Thompson: Really,

Jeffrey Jentzen: That was one of the, the major cases that was brought up of the science around the investigation and the, you know, political influences that were, that were present. I certainly think that that was one of the major cases that pushed forward.

Marcy Thompson: Why is it important for the person who is in charge of a death investigation in this way, in any kind of forensic capacity, why is it important for them to be educated in, in any other form of higher education?

Jeffrey Jentzen: Well. Death investigation, like any other profession, is based on training, experience and the literature.

And in order to be specialized in that, in order to be learned, you need to do all of those three things. The training is important because anything that the individual says in court is basically considered to be evidence. If that evidence is flawed, it will affect the outcome of the trial.

Marcy Thompson: I'm gonna go back a little bit and ask you about this Department of Legal Medicine that was started and funded by Frances Glessner Lee. Knowing what we know now, I guess we know that the needle wasn't moved enough, but back then, did it move the needle on legitimizing this profession?

Jeffrey Jentzen: Well, it certainly did. She was an early proponent of improved death investigation. She, of course, was interested in it a long time prior to that with her training programs and, and that that would put more people into the field.

Marcy Thompson: In the mid 1990s, Jentzen and his colleague, Steve Clark, were frustrated by the lack of education death investigators exhibited in the field, so Jentzen and Clark began to develop rigorous sets of guidelines for investigators, checklists of sorts that were adopted nationwide and are still used today by the Department of Justice.

Jeffrey Jentzen: These guidelines were rolled into a certification program, which is now the American Board of Medical Legal Death Investigation, and these guidelines are the foundation for the certification program.

Marcy Thompson: I'm not suggesting at all that Frances Glessner Lee had anything to do with your guidelines being created, but I will say that. It was certainly the, a dream of hers that such guidelines would even exist.

Jeffrey Jentzen: Well, I think she was the foundational person, the, the seminal aspect of death investigations because she was a private individual who saw a need in a government entity and used her, her time, efforts, and money. To facilitate this kind of program.

Marcy Thompson: So the question for me is how much impact did she have on helping push this field of science forward, even though she wasn't a scientist herself?

Jeffrey Jentzen: Well, I think she had a lot of impact because individuals started training in those areas and then they would travel across the country and they became the next generation of forensic pathologists, I talked about how most citizens get frustrated with the lack of justice. I think it's human nature that you, you feel if somebody's been violated, there needs to be some remedy on, on the pain that was inflicted on them.

Katie Hafer: It definitely brings us a long way from a girl doing needle work in Chicago to a woman who dedicates her life in service of the greater good. But I have to ask, do you think it was hard for her to stay behind the scenes?

Marcy Thompson: I think it was hard for her to gain traction for the field no matter what she did. But she wrote something towards the end of her life that I found really poignant. She wrote, “Being a woman has made it difficult at times to make the men believe in the project that I was furthering … the discouragements have been plentiful and severe.” So she was, she was bummed.

Katie Hafer: She was bummed. But I mean, forensic science became huge and yet she was discriminated against, and she remained in the background. And that is a tune. We can hum by heart at this point. This has been so fascinating and now we have a much better understanding of her contribution to forensic science, and it wasn't just that she liked to create creepy murder scenes.

Marcy Thompson: Yeah, I mean, she was motivated and dedicated to using science and to really creating a branch of science to bring people to justice.

Katie Hafer: Marcy, thank you so much.

Marcy Thompson: You're welcome. It was really my pleasure. Thanks Katie.

Katie Hafer: For more on lost women scientists and forensics, check out our episode on the chemist Mary Louisa Willard. She did forensics as a side hustle starting in the 1930s. And in that episode you'll hear more from Bruce Goldfarb who was a guest. You can find the link on our website LostWomenofscience.org.

Marcy Thompson was senior producer for this episode, and Deborah Unger was senior managing producer. David DeLuca was our sound designer and sound engineer. Our music was composed by Lizzie Younan. We had fact checking help from Lexi Atiya. Lily Whear created the art. Thank you as always to my co-executive producer, Amy Scharf, and to Eowyn Burtner, our program manager.

Thanks also to Jeff DelViscio at our publishing partner, scientific American. We're distributed by PRX for a transcript of this episode and more information about Frances Glessner Lee. Please visit our website, lost women of science.org and sign up so you'll never miss an episode. And oh, yes. Don't forget to click on that all important donate button. See you next time.

Listen to the Next Episode in this Series

More Episodes

Listen to the complete collection of episodes in this series.