September 25, 2025

Opening Doors to Computer Science

September 25, 2025

Opening Doors to Computer Science

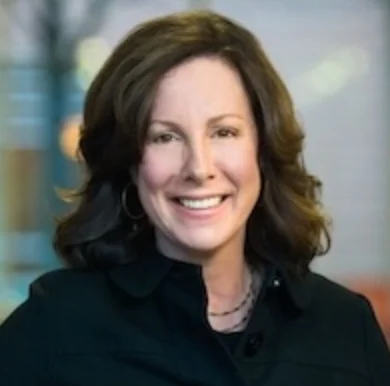

Carla Brodley, founder of the Center for Inclusive Computing at Northeastern University, explains how to make computer science education more accessible to everyone.

Episode Description

In high school, Carla Brodley was almost shut out of computer science when boys took over all the computers. But she rediscovered her love for the field in college and has made it her mission to open doors for others. At Northeastern University, she founded the Center for Inclusive Computing, which now partners with more than 100 institutions to make computer science more accessible. As a result of Brodley’s push to introduce more flexible degree programs, more women — and especially more women of color — have not only enrolled but stayed in the field.

Now, with support from Pivotal, a group of organizations founded by Melinda French Gates, Brodley is aiming to scale up her efforts. Today she joins Lost Women of Science host Katie Hafner to share her journey, new paths to computer science, and how AI fits in.

Katie is co-founder and co-executive producer of The Lost Women of Science Initiative. She is the author of six nonfiction books and one novel, and was a longtime reporter for The New York Times. She is at work on her second novel.

Laura Isensee is a journalist based in Houston, Texas. She has covered education, politics and diverse communities, and her work has been published by NPR, Reveal, Marketplace, the Miami Herald and Houston Public Media, among others.

Carla E. Brodley is a Professor of Computer Science and Founding Executive Director of the Center for Inclusive Computing (CIC) at Northeastern University. The CIC partners with over 100 universities to increase access to computing education. Dr. Brodley’s interdisciplinary machine learning research led to advances in many areas including computer science, remote sensing, neuroscience, digital libraries, astrophysics, computational biology, chemistry, and predictive medicine.

Katie is co-founder and co-executive producer of The Lost Women of Science Initiative. She is the author of six nonfiction books and one novel, and was a longtime reporter for The New York Times. She is at work on her second novel.

Laura Isensee is a journalist based in Houston, Texas. She has covered education, politics and diverse communities, and her work has been published by NPR, Reveal, Marketplace, the Miami Herald and Houston Public Media, among others.

Carla E. Brodley is a Professor of Computer Science and Founding Executive Director of the Center for Inclusive Computing (CIC) at Northeastern University. The CIC partners with over 100 universities to increase access to computing education. Dr. Brodley’s interdisciplinary machine learning research led to advances in many areas including computer science, remote sensing, neuroscience, digital libraries, astrophysics, computational biology, chemistry, and predictive medicine.

Further Reading:

Center for Inclusive Computing: Five Year Report, Northeastern University, May 2025.

A Grasshopper in Tall Grass, Lost Women of Science’s season about Klára Dán von Neumann who wrote the first modern-style computer code in the 1940s.

Transforming Trajectories for Women of Color in Tech, The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2022.

In Byron'’s Wake: The Turbulent Lives of Lord Byron's Wife and Daughter: Annabella Milbanke and Ada Lovelace by Miranda Seymour, Pegasus Books, 2018.

Episode Transcript

Opening Doors to Computer Science

Carla Brodley: It turns out that because of the way our systems have worked in this country, that the people most often who've not had access to computer science in high school are the people that would, if we could make it so that they enjoyed and persisted in computer science would change the demographics.

Katie Hafner: I am Katie Hafner, and welcome to the latest episode of Lost Women of Science Conversations where we talk with authors, artists, and others who've discovered and celebrated female scientists in books, poetry, film, and the visual arts.

Today I'm joined by Carla Brodley. She's a computer scientist and the founding Executive director of the Center for Inclusive Computing at Northeastern University in Boston. Carla has led the center to impressive success, not only to draw more women and women of color into the study of computer science, but to retain them.

The center partners with more than a hundred universities and institutions across the United States. And at those partner institutions, the number of women and people of color studying computer science who complete their degrees has increased dramatically. Today we're going to learn what's behind this success, what's next for inclusive computing and why it's all very personal for Carla Brodley.

Carla, thank you so much for joining me today. Actually, in person at WBUR in Boston, one of my favorite radio stations that I grew up with, I hasten to add.

Carla Brodley: I'm delighted to be here, Katie, and to talk about a subject that I love.

Katie Hafner: I have to say, Carla and I go pretty much way back. We've been talking about this intractable, uh, I don't know if you'd agree with me that it's still an intractable problem of women in computing for a while.

I've been writing about it for a long time, actually, since my daughter was born 32 years ago. This problem of attracting women to, and mostly retaining them. Computing and I wanted to start out by asking you your story and how you became a computer scientist.

Carla Brodley: I always loved as a kid playing with blocks and building things, and I think my parents thought I was gonna be an architect because I loved math and I loved making things with my hands. And I went to high school in Bloomington, Indiana and I took a computer science class 'cause my father suggested it. And I was in ninth grade and this was a huge high school, 2000 people.

And I had gym right ahead of my computer science class and. The gym was about as far from the math department as you could possibly get in this large sprawling, you know, rural high school. And I would run and I would get to the class and both computers would already be taken and there were nine other students in the class, and they were all boys and perhaps they hadn't gone through puberty yet and understood the value of the nerd girl in their future, and they did not allow me to touch the computer. And so I talked to the teacher who was a math teacher and mostly just sat there and let us do what we wanted to do, and he said I needed to work it out with the kids.

So I wrote my programs by hand and I debugged them by hand and it was fun, but it was fairly discouraging and I didn't go on.

Katie Hafner: Just to be clear, you wrote them and debugged them by hand and you still got an A, right?

Carla Brodley: Correct. I got an A. And at that point, frankly, computer programs were fairly simple and the ones that they would have you write in grade nine were very simple.

So you could do that and. We moved to Boston when I was 16. I went to a wonderful, more liberal arts focused high school, and I've always loved to read. So when I headed to McGill University, I decided to major in English and my parents rolled their eyes and tried to suggest that I do math.

Katie Hafner: What a reversal that you, it's not like you wanted to do something in science and they said, no, no, no. A girl doesn't belong in science. You headed to English. Right? And they said …

Carla Brodley: And they just rolled their eyes and said, you're not very good at English, you're much better at math. What are you doing? And I was rebelling as 17 year olds do. And that comes to one of the principles that I've always said as part of the work that I do.

Now, why do we let 17 year olds decide who goes into tech? A 17-year-old often is making decisions that are not the best for their future. So I got to McGill and I was in my English classes and I love to read, but I don't really like to write that much. And so I didn't do very well, so I thought, well, this isn't very practical.

I think I'll be an econ major. And then my roommate, who was a metallurgical engineering student, came home one day and she threw this pack of cards down on the table and she looked at me and she goes, Ugh, you would like computer science? And I thought, huh. I don't know. Maybe I would

Katie Hafner: You mean a pack of computer punch cards?

Carla Brodley: Yes. Uhhuh. I am that old. And for those who are much younger, a little bit about punch cards. So back when your grandparents were, um, studying computer science, the way that, um, computers worked was you had these punch cards and each row, or each column, I've forgotten now, which it was, uh.

You could punch out one little part of it and then that would be. Like a letter and you'd have a whole bunch of letters, and that would be a computer instruction on each card. And then you'd have a stack of these and you'd feed them through a card reader that would look for the holes, translate that into the electrical impulses of zeros and ones, which is the language that computer understands, and from that execute the code.

Katie Hafner: So punched or not punched. Punched or not punched. Mm-hmm.

Carla Brodley: Now interestingly enough, if you dropped those cards on the floor, you spent a long time reordering them.

Katie Hafner: Uhhuh. I can imagine. Yeah. So imagine,

Carla Brodley: You know, an analogy would be you've written a paper and you've got words, and then you accidentally drop them on the floor, all the words individually, and now you have to put them back into the sentences.

Not fun to drop those cards.

Katie Hafner: So your roommate, whose name was.

Carla Brodley: Paula Magdi.

Katie Hafner: So Paula, this metallurgical engineering student, she throws these computer cards on the kitchen table and says, okay, this is something you, Carla would like, and you then

Carla Brodley: It was not a compliment. Let me just make that very clear. So I thought, huh, that's interesting. So I signed up to take Fortran programming. We were on terminals. Mm-hmm. So I didn't have to do the cards. I'm not sure I would've loved computer science, had I had to do the cards, but I was able to program. By the second program, I still remember the second program was Newton's method, which is a way of mathematically solving integration. I was hooked. I was like, this is so much fun. And by the end of the semester, and it was my second semester of my second year of university, I remember calling my mother and saying, I really think I should change my major to math and computer science. And my mother was like. Well, why do you think that? I'm like, it's so exciting. It's so fun. I can't wait to do the assignments. She says, it's a no brainer. You should do this. Oh, and so I did, and it was the best decision I ever made. Now I had straight A's in everything.

Katie Hafner: Okay, so this is so great hearing your story. Clearly you were inspired to use that inspiration that you had to become an educator and build an education program and a curriculum that makes computer science more inclusive and supportive. Uh, so is that correct?

Carla Brodley: It is correct. When I became Dean of Cory College of Computer Sciences at Northeastern, and now I had the ability to work with the university, work with the faculty to think about how do we make it such that everybody could discover, have a sense of belonging and persist in computer science.

And in particular, I also wanted to think deeply about the problem of what if I hadn't discovered computer science? What if I'd graduated with that degree in economics? But then later I discovered computer science. And that was the birth of really thinking about the Master's in computer science for people who didn't study computer science as undergraduates.

And the program had already had a nascent start at the university before I got there, and they were thinking about this program as a way for people to switch fields in STEM. When I took over, I changed it to be, you could be from any field, you could be a theater major, you could be a dance major, you could be a business major.

And how would we prepare you to join the direct entry Master's students? Those that came with an undergraduate degree in computer science to thrive, persist, and graduate with a master's and go work in industry.

Katie Hafner: And what year was this?

Carla Brodley: This was in 2014.

Katie Hafner: Oh, so relatively recently. Yeah.

Carla Brodley: So we started small because I wanted to make sure that companies were gonna like this type of graduate

Katie Hafner: Companies, meaning those who would be hiring.

Carla Brodley: Yeah. And it turned out they were more popular with companies than the students who had done computer science throughout.

Katie Hafner: This is reminding me so much of kids who major in something else and then go on to get a post back for going to medical school. My own daughter majored in religious studies and went on to go to medical school and they loved her application because she had this sort of very rich different background. Do you think that's part of it?

Carla Brodley: Very much so. The industry loved the diversity of thought that came from these students. This program is called the Align Masters in Computer Science at Northeastern University, and I spoke to one of our biggest employers, which was Amazon and they told me that when you have an employee who maybe majored in English or history or something in the liberal arts and then gets a computer science degree, that their ability to think about the problems and their ability to talk about the problems is at a whole other level than someone who's just studied computer science.

And then if you think about the students that maybe had an undergraduate degree in biology and chemistry, and now they have a master's in computer science with a specialty in data science. You know, who does the biotech company or the pharmaceutical company wanna hire is the person who can understand both sides of what it is they're trying to do.

Katie Hafner: The very human side, and I think this is actually a good time to interject with an experienceI had recently where I gave a commencement speech at San Francisco State University to the computer science department. And when I was preparing it, I had long conversations with the chair of the department who was so kind of down in the dumps about his graduates four years ago. They enter computer science with just such high hopes and enter AI into the equation. So now these kids are having trouble finding jobs because of AI. And I said to him, should I even mention AI in the speech? He said, better not.

Carla Brodley: First of all, I think that it's not clear to me that AI is what's taking the jobs, even though that makes a fancy headline. I think that we're in an interesting time where there was a lot of hiring during COVID in tech because the whole world thought we were just gonna be all tech all the time. So, I think some of the layoffs that have happened are corrections of the over hiring. And second, I think there's a lot of uncertainty in the business world right now with high interest rates and an inability to know exactly what's gonna happen with the economy.

And so companies are not hiring a lot. I think that there will still be jobs. I think we're in a somewhat unique place where AI is happening at the exact same time as all of these economic factors.

Katie Hafner: Interesting.

Carla Brodley: And I don't think we're gonna know for another year or two whether it's actually the business environment that we're in right now, and the uncertainty around the future of business and how we're gonna proceed as a country versus how AI is impacting the workforce. So I, I think that it's an interesting time, but I do think very much so that the student that is trained in computer science and another field is gonna be the most desirable on the market.

Katie Hafner: So let's talk more about that training and how CIC is changing how students are learning computer science. What do you see as the biggest barrier? When you look at a traditional computer science degree program,

Carla Brodley: The number one biggest barrier for a student who's new to computer science, and that is more often women or people from races and ethnicities that have been historically minoritized in tech and students of all genders, races, and ethnicities from high schools that don't have computer science. And only 56% of our schools nationwide in the United States offer computer science in high school. And it's often an elective. And my own sons told me, taking computer science in high school was social suicide.

So the only way we're gonna change who goes into computer science in high school is if it's required for all students.

Katie Hafner: That's a classic pipeline problem.

Carla Brodley: That is a classic pipeline problem. So now fast forward and students are in university and maybe they're interested in computer science and they walk into the class and maybe they're part of the majority group, maybe they're not, in terms of demographics and there's people that are in that classroom that are talking about, you know what they got on the AP Computer Science. They're asking questions like, is that a Boolean? Is that an inherited class? And the student who's new to computer science is sitting there and saying, “a Boolena”, what’s an inherited who? And the analogy I like to use is, imagine you're 18, you've gone to university, and you decide to take Japanese or French or Spanish, and you walk into the classroom and you look different than everybody in the classroom, and everybody else is already talking in that language.

Katie Hafner: So this seems to go straight to the heart of your philosophy, which is this idea that it's not the person who's the problem, that it's the curriculum that's too rigid. That, that whole idea of a flexible curriculum, is that right?

Carla Brodley: It's the system. It's the way the institution has decided to offer computer science.

There are several ways to take that feeling out of the classroom. One way is to just make multiple sections of your first class. Let's call that CS one and have students self-select whether they would like to be in a class with true beginners or in a class with more experienced students. And then the key is that they learn the same things. They have the same assignments and the same exams. All you've done is remove the stress of sitting in a room with a bunch of know-it-alls. And there's a few other solutions to this problem of having this distribution of prior experience with some people having quite a bit of experience and some people completely new to coding. We have about five different approaches for universities to take. And when we work with universities, we try to figure out what's gonna work for them in terms of the approaches.

Katie Hafner: Yes, because every university has its own individual sort of set of problems

Carla Brodley: And what language they use and how that impacts what the AP computer science test is in, and whether they have a lot of transfer students from community college.

So every university context is really important, but the principle is the same: Don't lump them all together.

Katie Hafner: Right. And don't just assume everybody does the same thing. I have actually watched you in action. I followed you once to one of these universities where you met with the computer science department and you're just so good at listening. You're almost like a therapist in a way.

Let's talk about required classes. Just an example: calculus for a lot of students, myself included, that class can feel incredibly intimidating. It's like organic chemistry from pre-med. It isn't essential for every computer science career, but it is required to complete the degree, and in your research, it shows up as one of the biggest roadblocks as.

Especially for women. Let's not forget, we're talking here about women and the retention of women. So why is that, and what do you think could make this hurdle a little less intimidating?

Carla Brodley: Only 20% of high school graduates have taken calculus, which means that the majority of people heading to university have not taken calculus. They may not even be what's called calculus ready, which means they've taken pre-calc, and so that means that students come to university. With various levels of prior math exposure and the biggest mistake the computer science department can make, whether or not they require calculus, that's not the biggest mistake.

The biggest mistake is tying progression in the computer science classes to progression in the math classes. Let me be more specific, requiring calc one before they can take the first computer science class or the second computer science class as a prerequisite. As a prerequisite, that's a mistake because it's not relevant to the first class and it's maybe not that much fun versus the first computer science class which is unbelievably fun if you're gonna like computer science,

Katie Hafner: Right?

Carla Brodley: Not all computer scientists like calculus.

Katie Hafner: Right. Yeah, that's such a good point. Like it's, so there's this really special switch that gets switched on when you are turned on a computer science. I think that's absolutely right. More after the break.

Katie Hafner: Okay, so here we are talking about curricula and formal teaching. Carla, I can't do this whole episode with you without asking you about figures in history. Uh, women in computer science, in the history of computer science. For instance, one of the women we featured was Klára Dán von Neumann who knew nothing about computing because it kind of didn't even really exist when her husband, John von Neumann, sort of taught her.

She did some of the very first modern style code on a computer in the 1940s. But she'd never been able to do what she ended up doing if she'd gone through all that calculus rigamarole, or she never even learned any of that. And there's another figure in history who I just found out about named Sharla Perrine Boehm. So you can tell me, have you ever heard of Sharla?

Carla Brodley: I don't think so.

Katie Hafner: Thank you. That's my point exactly. It turns out that she was instrumental in developing packet switching, and her name is on some of the early packet switching papers. Uh, so, excuse me. Like it was somebody who brought her to our attention. And do you think that there are a lot of women out there like her, like Klára, who did important things in computing early on, who we still need to dig and find? I would imagine so

Carla Brodley: Given that I didn't know who this person was.

Katie Hafner: Right? And you look so sort of chagrined and contrite, like, I'm sorry, I don't know. But of course you shouldn't be chagrined and contrite because I didn't know, and I wrote a whole book about it. And I love discovering them; and talk about persevering. I mean, these women must have done something really, um, what's the word? Uh, unusual to achieve what they achieved. And I think that what you are doing with CIC is just smoothing the way.

Would you agree with that?

Carla Brodley: I think that I'm helping make sustainable systemic change in the institutions themselves so that the barriers that they've unwittingly and unknowingly constructed. So, not intentionally. I don't think so. In fact, when it's explained to them why having calc one as a prereq for the first computer science class as a mistake, they get it. They just hadn't thought about it. They did not do it on purpose. So an example of a barrier is you all can try CS one and CS two, the first two classes, and you should take calc one and calc two. And then depending on your GPA, you can get the golden ticket of being the computer science major. And that's biased toward people who've already had computer science in high school and who's already had computer science in high school

Katie Hafner: Boys,

Carla Brodley: Asian boys in particular.

Katie Hafner: Oh, interesting. Yeah, of course. The very ninth graders who wouldn't, those ninth graders

Carla Brodley: That wouldn't let me touch the computer.

Katie Hafner: Uh, okay. So I hear you wanna make a sustainable, inclusive computer science program at institutions all over the country. What real world results have you seen so far?

Carla Brodley: So there are 50 universities offering or about to offer the bridge to the Master's program for people who didn't study computer science. And so that means that those people will be new to computer science and they will come from all, you know, demographic identities, and that's really exciting.

And at the undergraduate level, at the schools that we've worked with for long enough to be able to have measurable results, which are, uh, 21 of our 35 schools that we've worked deeply with at the undergraduate level, we have seen incredible increases in groups that have been historically underrepresented in tech and in particular, one of my favorite statistics is African American women from fall of 19 to fall of 2023, have gone up by 136% and yet wait 136. And you could say, well, that's because maybe the number was very small, but that's 455 net new Black women in computer science at these 21 universities.

Katie Hafner: That's pretty incredible. Yeah. So hats off to you.

So what are some other new initiatives that you're working on that you're excited about?

Carla Brodley: I'm super excited about two new initiatives, and both of them are really designed to make people versatile in today's world. There are also ways to help students discover computer science because if I hadn't had that experience where my roommate insulted me into trying it, I would've never discovered it.

Katie Hafner: Shout out to Paula.

Thank you, Paula. And so I started thinking about this, and when I got to Northeastern there was this idea of a combined major. And when I looked at this, we had 12 of them when I joined as Dean in 2014. And they were all the things that computer scientists thought made sense. And I was like, such as? Physics and computer science, electrical engineering and computer science. Math and computer science. And then there was this one design and computer science in our college of arts, media and design. And I saw that all the demographic diversity was in that one, especially the gender diversity. And I thought about it and I'm like computer sciences for everyone and everything.

And so during my time as Dean, I added 36 more, like English and computer science, cybersecurity, criminal justice, data science in every field of stem. And now, fast forward to today, these programs kept growing. We have 46 different interdisciplinary majors.

Katie Hafner: Really

Carla Brodley: Over 50% of our students are now pursuing these interdisciplinary degrees. They're very popular with industry. Again, these students get hired at the juncture of their fields or in one or the other of their two fields. I wanted to take this idea out to other universities to show that it could be done at large, complicated public universities of all sorts. So we created a portfolio of universities.

We have eight of them in the portfolio. They're in different parts of the country. They're different types of universities. Some are top ranked universities in computer science, some are flagship, some are more open access, and we're working with them to do all of the work under the hood to enable these interdisciplinary majors.

And we have several of these universities starting offering this fall and others are on track for next fall. And offering these interdisciplinary majors like computer science and neuroscience, um, psychology and computer science.

Katie Hafner: That's fascinating. So tell me about the second initiative you're excited about.

Carla Brodley: Well, I think it's on everybody's lips right now: AI

Katie Hafner: uhhuh

Carla Brodley: And thinking about how do we make sure that women are going into technical AI education, or all people are going into technical AI education. Some of the things we're thinking about are: can we create specialized math classes for AI that don't take the same amount of time as going through the topics sequentially in the math department. To really do machine learning, you need to have ideas from calc one, from calculus two, from linear algebra and probability and statistics.

Katie Hafner: But not everything.

Carla Brodley: But not everything. And not necessarily the way the math department would teach them with the proofs. We need to know how to apply them and to understand them in computer science. And so we're starting to think about an initiative where people create math for CS, math for AI classes as part of this initiative otherwise students can't take their first AI class until their fifth, sixth, or seventh semester in university, and that's too late.

We're also thinking about how do you bring AI into the very first courses so people can see the applicability of machine learning algorithms perhaps in medicine. Or in science or in the digital humanities,

Katie Hafner: And you just got a really wonderful, large investment. Tell us about that.

Carla Brodley: We just received a wonderful gift to support our initiatives both around the systemic change in undergraduate programs and in particular around the systemic changes needed to be made in AI from Pivotal, which is Melinda French Gates's organization, where they've really, really invested in women in, in innovation and tech.

Katie Hafner: Shout out to Melinda French Gates and Pivotal, for doing that. I mean, she has done tremendous work in helping women thrive in the workplace, right?

Carla Brodley: She's one of my heroes. We have been very fortunate to get an investment substantial enough that we'll be able to move the needle in AI across many universities in this country.

Katie Hafner: That is amazing. I don't wanna be a Debbie Downer here, but it does make me sad to think about other sources of funding that have been drying up. I don't think we can have this conversation without talking about that. So many of these publicly funded initiatives are suffering. What are your thoughts on not just that in general, but about the backlash against diversity and equity efforts?

Carla Brodley: I think that it, there are many ways to achieve diversity and equity in terms of initiatives, and the CIC has always focused on fixing the system rather than doing things around individuals. And it turns out that when you fix the system, you often get the results that you're hoping for. We didn't do anything specific for black women and yet they went up by 136%. We just stopped doing things that don't work for true beginners. And true beginners can be white men as well. And so it benefits everybody. So there's things that we can be doing that are not program or individual demographic specific that will change it and make it better.

Katie Hafner: Have you had to go back as so many others have and scrub out some of this language on your website? Words like inclusive, and obviously you can't because it's in your name.

Carla Brodley: We kept inclusive because we really mean inclusive in its largest sense. We include everybody. We include white men from every state in this country. Right? It really is inclusive. We always had the mission that we wouldn't work with any particular group.

That was always my desire. It was to open up new pathways so that people who had felt excluded could come in, but people who didn't feel excluded but just hadn't noticed it yet could come in as well.

Katie Hafner: So to wrap up, I wanted to ask you to give advice to educators at all levels, whether it's primary education all the way up to advanced degrees. What would be your best advice when it comes to opening up young minds?

Carla Brodley: I would say look at the systems and the regulations and the way in which you're offering your programs, and think about whether you really have a door that's open to everybody to explore, to discover, and to persist in whatever makes their heart sing, and to make no assumptions that someone who's new to a field isn't good at the field.

Katie Hafner: Well, Carla Brodley, I would like to thank you so much for coming on to lost Women of Science Conversations to talk to us about this extremely important topic and all that you're doing.

Carla Brodley: Katie, it's been my pleasure to be here with you. And I just wanna share a little personal anecdote that last night my book group met and because I told them you were interviewing me, we decided to listen to the very first season of Lost Women of Science as our book for this session.

And we spoke about it last night and oh my God, two of us are scientists that are in the group, and we talked about Rachel Maddow's you know dude Wall and and the two of us that were scientists who had leadership positions shared that we weren't on the dude wall and had to advocate for ourselves to get up there. And I just wanted to say thank you, not only for today, but for the wonderful discussion that we had last night at my book group.

Katie Hafner: That's so nice to hear. And just to clarify, the dude wall refers to all the portraits that you see when you go into, say, a museum or a university or a medical school of all the basically white men who are up on the wall.

And thank you so much. What a very nice thing that your book group did that. And with that, I would like to thank you for that and also so much for coming on Lost Women of Science Conversations.

Carla Brodley: It's been such a pleasure to be here.

This has been Lost Women of Science Conversations. This episode was hosted by me, Katie Hafner. Our producer was Laura Isensee and Hansdale Hsu was our sound engineer. Special thanks to Michael Garth and Glenn Alexander and the rest of the production team at WBUR in Boston where this episode was recorded.

Thanks to Jeff DelViscio at our publishing partner, Scientific American. Also special thanks to our senior managing producer, Deborah Unger, my co-executive producer Amy Scharf and our program manager Eowyn Burtner. The episode art was created by Lily Whear and Lizzie Younan composes our music. Lost Women of Science is funded in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Anne Wojcicki Foundation. We are distributed by PRX.

If you've enjoyed this conversation, please go to our website Lostwomenofscience.org and subscribe so you never miss an episode. That lostwomenofscience.org. And please give us a rating wherever you listen to podcasts. Oh, and don't forget to click on that all important donate button that helps us bring you even more stories of important female scientists. I'm Katie Hafner. See you next time.

Listen to the Next Episode in this Series

More Episodes

Listen to the complete collection of episodes in this series.