January 29, 2026

Layers of Brilliance – Episode One: The Chemical Genius of Katharine Burr Blodgett

January 29, 2026

Layers of Brilliance – Episode One: The Chemical Genius of Katharine Burr Blodgett

Born to a family with a tragic past, Katharine defies the expectations of her upbringing as an upper-middle class girl to make chemistry and physics the center of her life.

Episode Description

In the first of this new five-part season, we trace Katharine’s early years as she picks up European languages, her early scientific education at a progressive New York school for girls and then Bryn Mawr, a women’s college. She seems destined to end up working at the General Electric Company’s industrial research lab, but first she must prove herself at the University of Chicago, where, in the middle of World War I, she works to improve the life-saving gas mask.

Katie is co-founder and co-executive producer of The Lost Women of Science Initiative. She is the author of six nonfiction books and one novel, and was a longtime reporter for The New York Times. She is at work on her second novel.

Natalia is a Peruvian journalist, editor, and writer based in Philadelphia. Her work focuses on gender inequality, labor issues, and reproductive rights. Natalia has worked as an editor for Radio Ambulante at NPR and in 2021, she won the Aura Estrada International Literary Award. She is currently working on her first book.

Sophia Levin is a journalist and teacher based in Washington, D.C. and Pittsburgh, PA. She has written about unions, infrastructure, and reproductive healthcare for The Tartan and PublicSource. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Creative Writing and History from Carnegie Mellon University.

Hannah is a Boston-based journalist with a background in storytelling, production, and strategic communication. She has reported on a variety of topics, including arts, culture, finance, and relationships between municipal agencies and communities. She studied journalism and art history at Northeastern University.

Katie is co-founder and co-executive producer of The Lost Women of Science Initiative. She is the author of six nonfiction books and one novel, and was a longtime reporter for The New York Times. She is at work on her second novel.

Natalia is a Peruvian journalist, editor, and writer based in Philadelphia. Her work focuses on gender inequality, labor issues, and reproductive rights. Natalia has worked as an editor for Radio Ambulante at NPR and in 2021, she won the Aura Estrada International Literary Award. She is currently working on her first book.

Sophia Levin is a journalist and teacher based in Washington, D.C. and Pittsburgh, PA. She has written about unions, infrastructure, and reproductive healthcare for The Tartan and PublicSource. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Creative Writing and History from Carnegie Mellon University.

Hannah is a Boston-based journalist with a background in storytelling, production, and strategic communication. She has reported on a variety of topics, including arts, culture, finance, and relationships between municipal agencies and communities. She studied journalism and art history at Northeastern University.

Peggy Schott is a retired chemist from Northwestern University and has written about Katharine Burr Blodgett and her achievements.

Josh Levy is a historian of science and technology at the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress.

Eric Furst is the William H. Severns Jr. Distinguished Chair of Chemical Engineering at the University of Delaware.

David Kaiser is a professor of physics and the history of science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Leslie Fields is an archivist and Head of Smith College Special Collections Public Services in Northampton, Massachusetts.

The Rev. Dr. Cathy H. George is a former Associate Dean at Yale University and priest who has served diverse settings ranging from suburban parishes to urban missions and prisons.

Further Reading:

The Remarkable Life and Work of Katharine Burr Blodgett (1898–1979), by Margaret E. Schott, E. Thomas Strom, and Vera V. Mainz from In The Posthumous Nobel Prize in Chemistry Volume 2, Ladies in Waiting for the Nobel Prize 1311, 1311:151–82. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society, 2018.

American Women of Science, by Edna Yost, Frederick A. Stokes Co, 1943.

The Old GE 1886-1986, by George Wise, Schenectady Historical Society, 2024.

Offerings to Athena: 125 Years at Bryn Mawr College, edited by Anne L. Bruder, Friends of the Bryn Mawr College Library, 2010.

Corporate Research Laboratories and the History of Innovation, by David Pithan, Taylor & Francis, 2023.

Electric City: General Electric in Schenectady, by Julia Kirk Blackwelder, Texas A&M University Press, 2014.

Episode Transcript

Layers of Brilliance – Episode One The Chemical Genius of Katharine Burr Blodgett

Nobel Series Film Host: Alfred Nobel was the inventor of dynamite. He left his entire fortune for a purpose not only Nobel in name, but noble in nature.

Katie Hafner : In 1939, the Nobel Prize Organization decided to celebrate some of its past laureates. They made this film featuring one of their winners, a chemist named Irving Langmuir, who won the prize in 1932, and in the film, he's standing in his lab at the General Electric Company, explaining some of the science that got him the prize. But he also describes another more recent breakthrough, the invention of non reflecting glass.

The discovery was monumental, but Irving Langmuir, well, he's not exactly Bill Nye the science guy. Dressed in a three piece suit, he looks less like a scientist than a businessman about to board a commuter train into work. And then there's his delivery.

Irving Langmuir: Uh, you need, uh, uh, a lighted surface. And, uh, you'll, I'll ask you to, uh, look over my shoulder.

Katie Hafner: He's clearly uncomfortable. He has trouble finding words, and then he calls for reinforcements. His colleague at General Electric, Katharine Burr Blodgett, someone who knows the science as well as he does. Maybe better actually, since she's the one who discovered this type of non reflecting glass in the first place.

She steps in to explain.

Katharine Burr Blodgett: You may have been noticing the reflection from Dr. Langmuir’s spectacles. But it is possible to treat glass in such a way that it will not reflect light. This is done by coating both sides of the glass with a special type of film.

Katie Hafner: Katharine Blodgett’s delivery is silken, confident. She's a hundred percent in command of her science. She is an inspiration, but for the duration of her career, Katharine Burr Blodgett worked in Irving Langmuir’s Shadow.

I'm Katie Hafner, and this is Lost Women of Science. This season, we're doing something slightly different. We’re bringing you the story of Katharine Burr Blodgett, and alongside her story, we’ll be telling you about the life and science of Irving Langmuir, the man she worked with for nearly four decades.

Katharine Blodgett was among the first female scientists employed at GE’s Research Laboratory when she was just 20 years old, and in 1926, a hundred years ago, she was the first woman to get a PhD in physics from the University of Cambridge. At GE, she made groundbreaking discoveries in material science. But while Irving Langmuir went on to win the Nobel Prize and rub shoulders with celebrities in and outside of science, and even star in a Kurt Vonnegut novel, Katharine Blodgett remained for most of her career, his apprentice, and she's been largely forgotten. And yet, when we dug into her story, what we found was as profound and dramatic as anything Vonnegut could invent, two scientists of equal brilliance, each tragic figures in their own way, as we shall see, working side by side in an era and a place that defined them both.

Katie Hafner: You, you aren't, Peggy, are you? No.

Unknown: No.

Katie Hafner: Okay. Hi, are you Peggy?

Peggy Schott: Katie? Hi yeah, Peggy.

Katie Hafner: Hi, nice to meet you.

Peggy Schott: Nice to meet you, finally.

Katie Hafner: Peggy Schott is a chemist, recently retired from Northwestern University. Like us, Peggy has a deep curiosity about Katharine Burr Blodgett, and she offered to join producer Sophia Levin and me at the Library of Congress on a scorching and humid Washington DC day last summer in our search for signs of a woman buried in the papers left behind by a man.

Katie Hafner: Um, where do we stash our stuff and, oh, these are the lockers. Okay.

Peggy Schott: Yeah. Did you get your photo thing?

Katie Hafner: I did.

Peggy Schott: Check in with this lady at the desk. And then she'll give you a key to a locker.

Katie Hafner: Okay, great.

Katie Hafner : Peggy has been researching the life and work of Katharine Burr Blodgett, and she ended up identifying with her so strongly that she once presented a paper at a conference as if she were Katharine herself.

Peggy Schott: Although I did not don a costume or make my hair gray or anything like that, I did act as though I was Dr. Blodgett, and it gave me a certain freedom to interpret her role.

Katie Hafner: As the production team at Lost Women of Science would learn, Katharine Blodgett can definitely get under your skin, in the best possible way.

Peggy offered to help us fill in the many blanks that still remained in Katharine’s biography and to bring her expert eye to all the science we were bound to encounter.

The Library of Congress in Washington D.C. preserves much of our nation's collective intellectual memory, more than 73 million documents and objects in the manuscript division, housed in temperature and humidity-controlled storage facilities. Materials of all kinds, including handwritten and typewritten pages and microfilm, are kept in neat rows of archival boxes, some stacked six shelves high. We went there on a needle-in-a-haystack mission, if ever there was one.

The haystack in question, the Irving Langmuir Collection in the Library of Congress, consists of 111 boxes filled with his correspondence, lab notebooks, and random other bits of relevant documents.

32,000 items in all, spanning 63 years.

As for the Katharine Burr Blodgett collection, they don’t have one.

In the course of reporting this season, we'd traveled to a catacomb-like archive in Schenectady, New York, a family storage unit in Eastern New Hampshire, and libraries in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, and Cambridge, England.

In each place, searching for traces of Katharine Blodgett’s intellectual and personal footprint. And we did find things, college records, yearbooks, personal letters, diaries, photographs, store receipts, pay stubs, people with stories to tell.

But Katharine's original lab notebooks. and there must be dozens of them, well, that's another story.

Let me explain. When you're researching the science someone has done, you can look at their publications through the years, the patents they've received, their PhD dissertation, things like that, to get a sense of their scientific journey.

But archives are crucial. When you can go through raw material, like laboratory notebooks, you can chart the course of their experiments, the triumphs and failures, and near misses.

Sometimes these notebooks are written like real diaries, which can be fascinating and revealing. We had no idea where those notebooks might be or whether they even still existed.

So we knew we'd be stitching Katharine’s scientific life together from scraps and shadows, listening for echoes of her in things written by Langmuir, tracing her presence in the margin of his notes. This is what it means to reconstruct a life when much of the record itself has gone missing.

It is true that Langmuir deserved his 1932 Nobel Prize for his discoveries. But we're telling the story of Katharine Blodgett because she deserves a spotlight of her own.

But why did Katharine dedicate the bulk of her professional life to the role of apprentice to Irving Langmuir? Without the notebooks, how will we know about the joy she found in science in general, and physics and chemistry in particular? Her love of experimentation? Her awe of Irving Langmuir?

Our dismay over the missing notebooks is shared by Josh Levy, who's the historian of science and technology at the manuscript division of the Library of Congress.

Josh Levy: In this case, it's especially frustrating, I think, because we have evidence that her work was documented, and the documentation seems to have been destroyed.

Katie Hafner: Seems is the operative word here. We aren't giving up hope that we'll find Katharine’s notebooks somewhere, not this early in the game. So as we entered the library's imposing, rule-laden reading room, having stashed our backpacks and lunch in lockers, we're thinking that maybe those Langmuir papers at the Library of Congress, which three of us would spend four days poring over, will give us a clue to just how all that science got done and what was in her brilliant mind and his. After all, they worked together shoulder to shoulder for decades. They even share billing for developing what are known to this day as “Langmuir Blodgett films,” which I need to tell you right off the bat, have nothing to do with the movies.

Katharine Blodgett made her biggest contribution to material science in the 1930s while working in the General Electric company's research lab, where she had the luxury of pursuing basic science with no specific product in mind. Building on work Langmuir had done in the 1910s, she developed a way for creating multiple layers of exceedingly thin films of substances, usually soaps, on a solid surface.

By exceedingly thin, I mean a molecule that's one 10,000,000th of an inch thick. Imagine, if you can, something 30,000 times thinner than a human hair. So these films are stacked one on top of the other, maybe dozens of them, maybe hundreds or even thousands, creating invisible coatings.

Eric Furst: This is every, you know, this is common today. This is a everyday sort of science and engineering today.

Katie Hafner: That's Eric Furst, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of Delaware.

Eric Furst: It is very much nanotechnology. And you know, I, we don't bat an eye at that type of thing. But wow, how pioneering that was, a hundred years ago.

Katie Hafner: The ability to build and control matter at a molecular layer-by-layer scale opened up entirely new frontiers for material science and eventually nanotechnology, advancing the cutting edge of electronics and sensor development.

In the early 1930s, Katharine Blodgett took Langmuir’s initial research and ran with it.

With her coating technique, she was able to develop non-reflecting glass, a huge discovery that paved the way for the non-reflecting properties of museum glass, camera, and eyeglass lenses.

In fact, any coating you see on a solid surface can trace its ideas back to the way Katharine prepared her built-up layers, which came to be known as Langmuir-Blodgett films. To put it very simply, the fruits of Katharine Blodgett’s foundational work are quite literally in everything all around you.

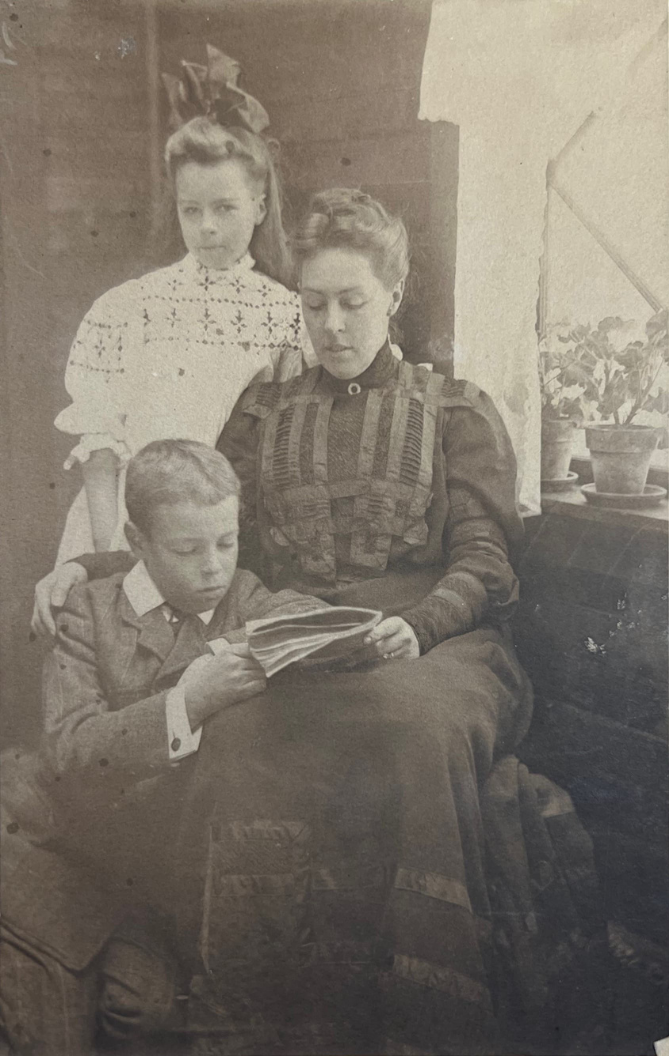

Katharine Burr Blodgett was born on January 10th, 1898, in Schenectady, New York.

Katharine and her older brother George were raised by their mother, a widow, who was also named Katharine. Her full name was Katharine Buchanan Burr Blodgett, and just because this might get a little bit confusing, we're going to call her Katharine Burr.

Katharine Burr was doing the single mother thing a good two decades before women even had the legal right to vote. Still, Katharine Burr, who came from money, and that didn't hurt, moved through life as if she had yet to be acquainted with an obstacle.

This is the role model Katharine Blodgett grew up with, a mother, ambitious in her goals for her children, and independent in her decision-making. Katharine Burr was determined to actively shape the course of her children's lives.

As far as we can tell, Katharine and her older brother George were held to equal academic standards. This too was unusual at the time. The boys got a college education, and the girls, they generally got married off.

Katharine Burr wanted every avenue open for her daughter, who would have the education and resources to pursue any field that sparked her interest.

I mentioned that Katharine Burr had money. And with money come options.

Here's Peggy Schott.

Peggy Schott: It's a kind of a complicated series of events, but, after she moves the children to New York City, after a time there, they went to France

Katie Hafner: Katharine Burr was convinced that the schools in Europe were better, and she wanted her kids to learn French, which they did. But when George marked his seventh birthday by announcing, “I now have seven years,” a direct translation from the way a French person would say it, Katharine Burr packed up the adventure and took the children back to the US for some English immersion.

Then, the threesome went back to Europe, Germany, this time adding a third language to the children's repertoire.

German, by the way, turned out to be a very handy language for Katharine to know when she got older. German was the lingua franca of science at the time, the language in which much of the world's most important research was published.

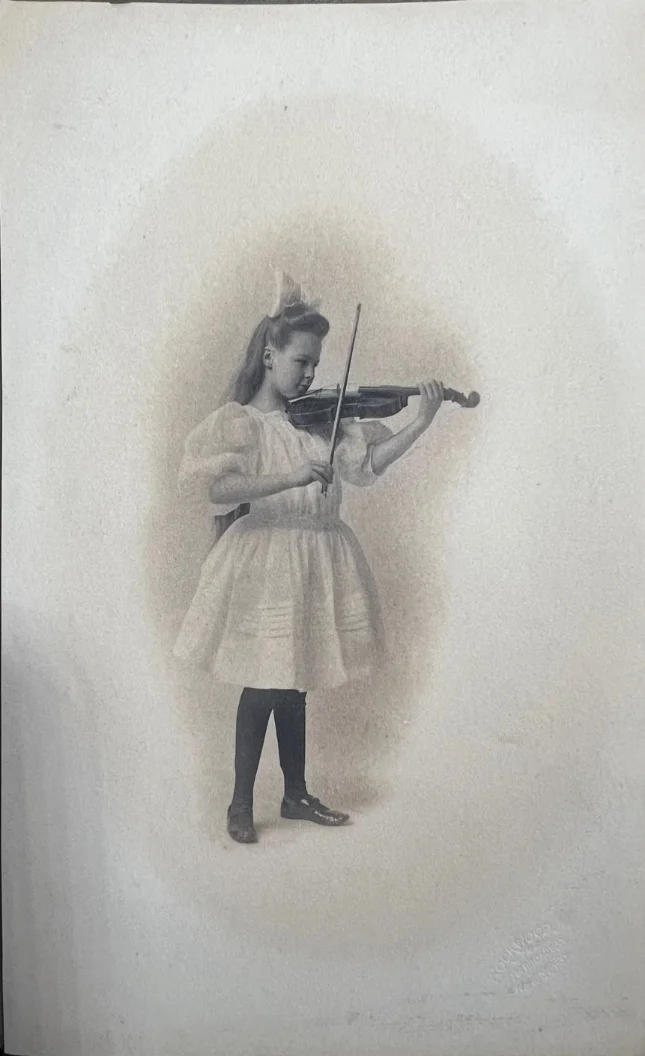

Katharine Burr didn't label her daughter a prodigy, but I think it's fair to say that, already as a young child, she fit the bill.

By at least one account, Katharine was reading at the age of two, and by the time she was four, she was writing as well.

In 1907, the family was back in New York for good. The Blodgetts moved into a swanky new apartment building on West 79th Street on Manhattan's Upper West Side.

The eight-story building was complete with telephones, an elevator, and a view of Riverside Drive near the Hudson River. Katharine was enrolled at the Misses Raysons’ School for girls on West 75th Street, a private school that educated its students all the way through high school. Here's Peggy Schott.

Peggy Schott: It was a school that was founded by three sisters. Their mother works there also. They had come over from England, and they founded the school in the 1800s.

Katie Hafner: The Rayson sisters were smitten with 10-year-old Katharine.

In 1908, one of the Rayson sisters wrote to Katharine Burr, and said. “You are a mother much to be envied in having a little girl, so absolutely reliable, and at the same time, so lovable.”

In choosing that particular school for her precocious daughter, Katharine Burr might not have known it, I mean, maybe she chose the school because it was so close to their apartment, who really knows, but she was setting the child up for success.

Peggy: The Misses. Raysons’ school was for women with a high academic standard. So they were really educating future leaders.

Katie Hafner: For one thing, the Rayson sisters based their teaching on the principle that to communicate clearly, one needs to think clearly.

Decades later, an executive at GE said Katharine was the most ordered, logical presenter he'd ever met. And for another, the school had a strong math and science curriculum. Katharine wasn't expected just to do spelling and needlework, learn some manners, or whatever it is girls did in school in the early 1900s.

Mathematics was her thing, and there was one teacher in particular.

Peggy Schott: Amy Rayson, who had a master of Arts in mathematics and who later was a member of the New York Mathematical Society.

Katie Hafner: My educated guess here is that it was Amy Rayson who nudged Katharine in the direction of math and science.

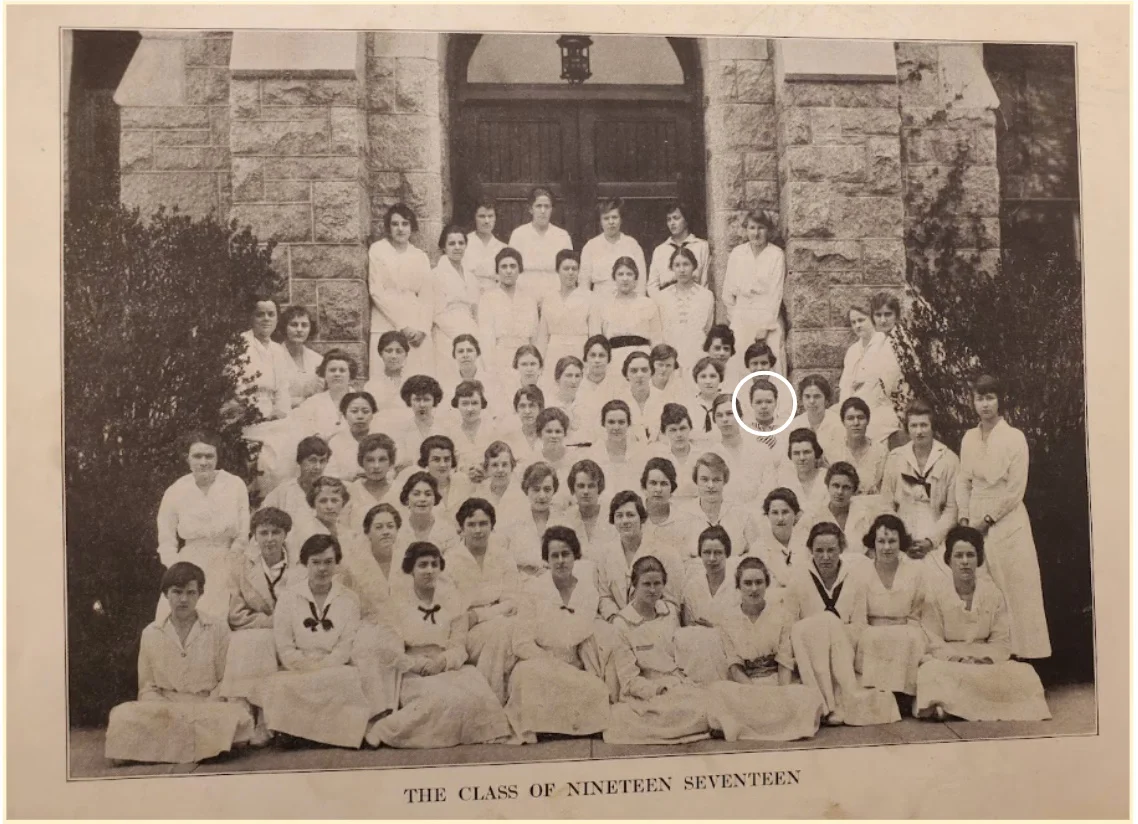

In the fall of 1913, with her brother George already off at Yale, Katharine Blodgett entered Bryn Mawr, a women's college near Philadelphia, known for its high academic standards. She had won a full scholarship, having beaten out smart kids from three different states.

She was all of 15 years old.

More after the break.

Katie Hafner: In 1913, 15-year-old Katharine Blodgett showed up at Bryn Mawr College. Bear in mind, this was a time when most universities barred women entirely, or relegated them to a second tier education. Bryn Mawr and a handful of other colleges offered women the opportunity not only to learn science, but teach it,practice it, even shape it.

And they did that by creating a world that was peaceful, insular, and rigorously academic. Our producer, Natalia Sánchez Loayza, visited the campus and she described it to me.

Katie Hafner: So is it? Is it tiny and bucolic?

Natalia Sánchez Loayza: Definitely bucolic. It's one of those little towns where the boundaries between college and the rest of the town aren't very clear. Just a few blocks from the train stop, you already can see the college sign, for example, that reads Bryn Mawr College.

Walking through Bryn Mawr feels like walking in a small, self-contained universe; it’s very peaceful.

Katie Hafner: And do you think that it looks the way it looked when Katharine was there?

Natalia Sánchez Loayza: Yes, there is a little bit of history in every corner. You're surrounded by these gothic stone buildings, and to me, I mean, it felt like I could have run into the next Katharine. And any girl there seemed to me, as a Katharine in the making.

Katie Hafner: Instructors at these places fostered a kind of intellectual ferment. And when I say ferment, I mean it literally. A slow, catalytic process that produces something new.

These colleges were places where ideas were bubbling up, where curiosity was alive, and where something important was quietly forming. At the same time, the instruction was deeply committed to the idea that women could and should be full participants in scientific inquiry.

Here's Peggy Schott.

Peggy Schott: The faculty at Bryn Mawr had a master's or a PhD in their subjects. The idea there was that the college wanted to give young women the same level and intensity and depth of education as young men were getting at that time.

Katie Hafner: David Kaiser, a professor of physics and the history of science at MIT, agrees.

David Kaiser: Names we kind of, rightly remember in the sciences, Vera Rubin helped us all understand the nature of dark matter, Henrietta Swan Levitt, who'd done extraordinary work in astronomy, Annie Jump Cannon, even earlier in the 1890s, we can stretch sort of before and after Blodgett’s own time, we can trace back to each of these schools.

Katie Hafner: Perhaps one of the most important aspects of an education at one of these colleges, known collectively as the Seven Sisters, was a strong tradition of mentorship.

Leslie Fields: If you were interested in, say, zoology then, then you had people who would really support you to continue that level of research.

Katie Hafner: That's Leslie Fields, an archivist who works in special collections at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts. Smith's a women's college and it's one of the seven sisters.

Leslie Fields: There's this kind of support that's there and certainly no question that women are completely capable. So I think that's very powerful.

And there are requirements in the curriculum for science classes of all kinds, and I'm, I'm saying science very generally, but there's, there were a lot of different options, and a lot of specific fields of study there with women who did very prominent levels of research in those fields that, that the students would've had as mentors.

Katie Hafner: All of that is what 15-year-old Katharine Blodgett stepped straight into in 1913, and she embraced it with everything she had.

Producer Sophia Levin reconstructed Katharine's four years at Bryn Mawr for me, starting from her very first day on campus.

Sophia Levin: Katharine arrived on a Monday, she moved into her dorm, and then she had one more day to settle. And then when nine o'clock rolled around on Wednesday morning, it was time for Katharine’s first class. It was a math course that focused on conics, which is a type of geometry. And something that's interesting to think about is that while all the students at Bryn Mawr were women, many of the professors were men.

Katie Hafner: Because…

Sophia Levin: Well, at the time, women were still unlikely to have PhDs, so the people who were sometimes most technically qualified in their field were still men.

Katie Hafner: And there was this one professor, who was one of her mentors, his name was…

Sophia Levin: Professor James Barnes.

Katie Hafner: James Barnes,, and he probably saw a pretty special talent.

Sophia Levin: Yeah, he was definitely one of her biggest mentors, if not her biggest mentor at Bryn Mawr, as well as one of her biggest advocates.

Katie Hafner: We know that she was getting a, a very rigorous science education, and that it kept her very busy.

But now we have to move on to the extracurricular Katharine.

Katie Hafner: Everywhere you turned, there she was?

Sophia Levin: There was Katharine in every corner of the college.

Katie Hafner: She not only took all these science courses, but did she manage the science club?

Sophia Levin: Yeah. But I know that you are looking forward to the rundowns.

So, Katie, are you ready for the full list?

Katie Hafner: Yes, I am ready.

Sophia Levin: Okay. So she was the manager of her class’s track team, all four years of college. She played water polo her sophomore year and then became the team's manager as a junior. She was appointed to be the assistant business manager of Bryn Mawr's newspaper.

Katie Hafner: Oh wow.

Sophia Levin: She was treasurer of her class's Senior Yearbook. She was one of 11 students to participate in the college's chess tournament.

Katie Hafner: Wait, chess, did you say chess? So she was a chess player?

Sophia Levin: I mean, she played in the tournament, so I would say so, yes.

Katie Hafner: We have no idea how she did?

Sophia Levin: Yeah, we don't, and the college news reported that Katharin co-wrote the student's favorite song, a reprisal of “As mother was chasing her boy around the room.”

Katie Hafner: That was like a popular song back then?

Sophia Levin: I suppose so.

Katie Hafner: Well, I couldn't resist. If Katharine wrote new lyrics to a song, I wanted to hear it. So I asked singer Ana Ana Tuirán to perform a cover. Here's the last stanza.

Ana Tuirán: So we're no better off than we were here before. And we’ll have to learn more of this stuff we abhor. With word lists and tutors and bills by the score, it’s a bore we are sore, and we won’t sing no more.

Katie Hafner: She had a great sense of humor.

Sophia Levin: Yeah, definitely.

Katie Hafner: What an amazingly well-rounded and energetic young woman she was. She contained multitudes all wrapped up in one person.

Katie Hafner: Speaking of multitudes, among the things we found in the course of reporting, this season was a small, thick, very, very old leather-bound notebook. When I picked it up, it actually started to fall apart in my hands.

It was Katharine’s Bible study journal from 1917, her senior year at Bryn Mawr. Pages and pages filled with Katharine’s small, neat handwriting.

She's quoting major theologians, parsing the historical Jesus, wrestling with miracles, et cetera. But what was most interesting to us was how she thought about the role of science in the life of a religious person.

I scanned some of the pages and sent them to the Reverend Cathy George, an Episcopal priest who has spent 40 years in ministry. Reverend George told me she was astounded by what she read.

She said, these aren't the scribbles of a pious teenager, they're the reflections of a deeply mature mind. I asked Reverend George if she thought Katharine’s science was at odds with her deep religious beliefs, and she said, “No. Not at all.”

Reverend Cathy George: Somehow, it's not a conflict for her. She's talking about miracles of the spirit, and she goes on to talk about miracles of natural phenomena.

It's just, for a scientist to be as deeply engaged as she is in being a Christian. To say you can't explain it all, is super interesting. It's just remarkable, especially in that era, that she had that capacity to engage with Christianity and not give up her science.

Katie Hafner: This is all the more remarkable because she's just turning 18, and although Katharine didn't believe science could explain everything, she was certainly determined to see how much it could explain.

Katharine was a seeker in the broadest sense. She was more than what you usually associate with the word scientist, someone with a fundamental curiosity to know how and why phenomena occur. As we would come to understand, Katharine Blodgett was also a scientist seeking to explain her own self, and that self was a complicated one.

And so, this brilliant young polymath, who had excelled at practically everything she turned her hand to, decided there was only one thing she wanted after graduation, a life in science.

Over the Christmas break of her senior year at Bryn Mawr, Katharine went job prospecting. She didn't cast a wide net. In fact, she had only one employer in mind: The General Electric Research Lab in Schenectady, New York, about 30 minutes northwest of Albany, one of the leading industrial research labs in the country.

As it happened, her father had once worked there, and she must have written one hell of a cover letter because she got a meeting with the lab's director, Willis Whitney, and with a research scientist named Irving Langmuir, at age 35, already a star.

It was America's Got Talent Physics Edition. No flashing lights or clapping and hooting and hollering audience, just a brilliant 18-year-old aspiring physicist, wowing two senior scientists with her dazzling rendition of “Let's talk about thermodynamics.”

Langmuir and Whitney were so impressed that they gave her a unanimous yes on the spot.

So as far as we can tell, there she was with nothing but a lifetime of encouragement. Absolutely nobody saying, “A woman can't do this.”

But their yes, came with a condition. The GE scientists told her to pursue an advanced degree, and then she could come work there.

And so she did. In the fall of 1917, she entered the University of Chicago's master's program in physics. What did Katharine research? It was very much driven by the necessity of those years. It was three years into World War I. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers were being exposed to chemical warfare in Europe.

David Kaiser: World War I was, was dubbed the Chemist's War, for all kinds of applications including, chemical weapons, but also things like gas masks to protect against chemical weapons.

Katie Hafner: That's David Kaiser, the science historian.

David Kaiser: So all kinds of properties about stuff in the air, gases that could be quite harmful. And how do you protect from them? Huge, huge importance.

Katie Hafner: And one of the most important ways to protect soldiers from dangerous gases—the gas mask.

These masks relied on a canister filled with activated charcoal, which works by a process called adsorption, in which molecules stick to a surface rather than sinking into it.

Sinking into something, absorption, is the word we're more familiar with. At Chicago, Katharine investigated how a gas mask filter actually worked when confronted with the complex chemical cloud of a battlefield. It was already known that charcoal could filter out toxins, trapping those toxic gas molecules on the surface of the charcoal.

Katharine’s research on harmless oxygen and nitrogen, the main components of air, paved the way for two vital advances for filter design.

First, when a mixture of gases hits the charcoal, they don't get trapped independently. Instead, the gases compete with each other, with the presence of one gas actually hindering the adsorption, or trapping, of the others.

This competition principle was crucial for engineers building canisters that had to simultaneously filter toxic gases mixed with normal air.

Second, Katharine discovered that the charcoal was more effective if the gas was introduced in smaller successive portions rather than all at once. Her study provided precise scientific rules for how air and poison interacted inside the filter, helping to improve gas mask technology.

So after Katharine’s stellar stint in Chicago, it wasn't surprising that, as promised, the GE lab came through with its job offer.

There was just one lingering point of negotiation. On July 16th, 1918, Katharine wrote to lab director Willis Whitney, telling him she planned to report for work, oh, sometime in the fall.

But he was impatient. He wrote back to her right away.

We asked Benjy, that's my stepson. He has a great voice to read it for us.

Willis Whitney: Dear Miss Blodgett, can't you come now? Of course, we should be glad to have you join us in the fall, but gladder, if you come soon. I think you would be worth at first about $125 a month.

Is this a bad guess?

Katie Hafner: How's that for being made to feel like you're wanted?

Sophia and I were talking about all of this, and she brought up something I hadn't thought of: Katharine’s mother. The two were as close as close can be for reasons born largely of tragedy. Here's Sophia.

Sophia Levin: I really wonder what Katharine’s mom said when she decided to visit Schenectady.

I wonder if Katharine even told her about the trip before she went, and if she did, did her mom encourage it, or was she more resistant?

Katie Hafner: And that was absolutely something to ponder.

Schenectady, New York, was a fraught place. Not as much for Katharine, who left as a newborn, but for her mother, Katharine Burr.

Next time on Layers of Brilliance.

Larry Hart: Now, I might as well get this over with, I wanted to talk to you a little bit more about your father.

Bill Buell: I know it was 1897, but still you could get a sense, an eerie sense of something bad happening there. Even if it was 127 years ago.

Maryanne Malecki: It was at night. Mr. And Mrs. Blodgett were already in bed. Mrs. Blodgett heard a noise, so she told her husband to get up.

Julia Kirk Blackwelder: What I think of is the terror and horror that the wife experienced. It's a wonder she didn't lose the child.

Katie Hafner: This has been Lost Women of Science. Our producers for this episode were Natalia Sánchez Loayza and Sophia Levin, with me as senior producer, writer, chief cook and bottle washer. Hannah Sammut was our associate producer. Elah Feder was our consulting editor. And David DeLuca Ferrini was our sound designer.

Lisk Feng designed the art. Elizabeth Younan is our composer.

Thanks to Deborah Unger, our senior managing producer, program manager Eowyn Burtner, my co-executive producer Amy Scharf, and marketing director Lily Whear.

We got help along the way from Gabriella Baratier, Benjy Wachter, Eva McCullough, Nadia Knoblauch, Theresa Cullen, and Issa Block Kwong.

A super special thanks to Peggy Schott, George Wise, Ellen Lyon, Cyrus Mody, David Kaiser at the Schenectady County Historical Society, Josh Levy at the Library of Congress, Ben Gross at the Harry Ransom Center at UT Austin, and Chris Hunter at the Museum of Innovation and Science in Schenectady.

And we're grateful to Deborah, Jonathan, and Marijke Alkema for helping us tell the story of their great Aunt Katharine. We're distributed by PRX and our publishing partner is Scientific American. Our funding comes in part from the Alfred P Sloan Foundation and the Susan Wojcicki Foundation.

Please visit us at lostwomenofscience.org, and don't forget to click on that all important, ever present donate button.

I'm Katie Hafner. See you next week.

Listen to the Next Episode in this Series

More Episodes

Listen to the complete collection of episodes in this series.